Primavera also known as Allegory of Spring, is a tempera panel painting by Italian Renaissance artist Sandro Botticelli. Painted ca. 1482, the painting is described in Culture & Values (2009) as “one of the most popular paintings in Western art“.It is also, according to Botticelli, Primavera (1998), “one of the most written about, and most controversial paintings in the world.”

Most critics agree that the painting, depicting a group of mythological figures in a garden, is allegorical for the lush growth of Spring. Other meanings have also been explored. Among them, the work is sometimes cited as illustrating the ideal of Neoplatonic love. The painting itself carries no title and was first called La Primavera by the art historian Giorgio Vasari who saw it at Villa Castello, just outside Florence, in 1550.

The history of the painting is not certainly known, though it seems to have been commissioned by one of the Medici family. It contains references to the Roman poets Ovid and Lucretius, and may also reference a poem by Poliziano. Since 1919 the painting has been part of the collection of the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, Italy.

Composition.

The painting features six female figures and two male, along with a blindfolded putto, in an orange grove. To the right of the painting, a flower-crowned female figure stands in a floral-patterned dress scattering flowers, collected in the folds of her gown.

Her nearest companion, a woman in diaphanous white, is being seized by a winged male from above. His cheeks are puffed, his expression intent, and his unnatural complexion separates him from the rest of the figures. The trees around him blow in the direction of his entry, as does the skirt of the woman he is seizing. The drapery of her companion blows in the other direction.

Next to this woman is another woman wearing a flowery designed dress that drapes over her body. She has a slight smile on her face while stepping towards the viewer and holding a grouping of flowers in her dress. The flowers on her dress and in her hand consist of pinks, reds and whites accompanied by the greens of the leaves.

Clustered on the left, a group of three females also in diaphanous white, join hands in a dance, while a red-draped youth with a sword and a helmet near them raises a wooden rod towards some wispy gray clouds. Two of the women wear prominent necklaces. The flying cherub has an arrow nocked to loose, directed towards the dancing girls. Central and somewhat isolated from the other figures stands a red-draped woman in blue. Like the flower-gatherer, she returns the viewer’s gaze. The trees behind her form a broken arch to draw the eye.

The pastoral scenery is elaborate. Botticelli (2002) indicates there are 500 identified plant species depicted in the painting, with about 190 different flowers.Botticelli. Primavera (1998) says that of the 190 different species of flowers depicted, at least 130 have been specifically named.

The overall appearance of the painting is similar to Flemish tapestries that were popular at the time.

Themes.

Various interpretations of the figures have been set forth, but it is generally agreed that at least at one level the painting is, as characterized by Cunningham and Reich (2009), “an elaborate mythological allegory of the burgeoning fertility of the world.” Elena Capretti in Botticelli (2002) suggests that the typical interpretation is thus:

The reading of the picture is from right to left: Zephyrus, the biting wind of March, kidnaps and possesses the nymph Chloris, whom he later marries and transforms into a deity; she becomes the goddess of Spring, eternal bearer of life, and is scattering roses on the ground.

This is a tale from the fifth book of Ovid’s Fasti in which the wood nymph Chloris’s naked charms attracted the first wind of Spring, Zephyr. Zephyr pursued her and as she was ravished, flowers sprang from her mouth and she became transformed into Flora, goddess of flowers. In Ovid’s work the reader is told ‘till then the earth had been but of one colour’. From Chloris’ name the colour may be guessed to have been green – the Greek word for green is khloros, the root of words like chlorophyll – and may be why Botticeli painted Zephyr in shades of bluish-green.

Venus presides over the garden – an orange grove (a Medici symbol).She stands in front of the dark leaves of a myrtle bush. According to Hesiod, Venus had been born of the sea after the semen of Uranus had fallen upon the waters. Coming ashore in a shell she had clothed her nakedness in myrtle, and so the plant became sacred to her.The Graces accompanying her (and targeted by Cupid) bear jewels in the colors of the Medici family, while Mercury’s caduceus keeps the garden safe from threatening clouds.

The basic identifications of characters is widely embraced, but other names are sometimes  used for the females on the right. According to Botticelli (1901), the woman in the flowered dress is Primavera (a personification of Spring) whose companion is Flora.The male figure is generally accepted as Mercury but has been identified as Mars by Beth Harris and Steven Zucker of SmARThistory.

used for the females on the right. According to Botticelli (1901), the woman in the flowered dress is Primavera (a personification of Spring) whose companion is Flora.The male figure is generally accepted as Mercury but has been identified as Mars by Beth Harris and Steven Zucker of SmARThistory.

In addition to its overt meaning, the painting has been interpreted as an illustration of the ideal of Neoplatonic love popularized among the Medicis and their followers by Marsilio Ficino.

The Neoplatonic philosophers saw Venus as ruling over both earthly and divine love and argued that she was the classical equivalent of the Virgin Mary;[9] this is alluded to by the way she is framed in an altar-like setting that is similar to contemporary images of the Virgin Mary.

In this interpretation, as set out in Sandro Botticelli, 1444/45-1510 (2000), the earthy carnal love represented by Zephyrus to the right is renounced by the central figure of the Graces, who has turned her back to the scene, unconcerned by the threat represented to her by Cupid. Her focus is on Mercury, who himself gazes beyond the canvas at what Deimling asserts hung as the companion piece to Primavera: Pallas and the Centaur, in which “love oriented towards knowledge” (embodied by Pallas Athena) proves triumphant over lust (symbolized by the centaur). It is, on the other hand, possible that, rather than her having renounced carnal love, the intense emotional expression with which she gazes at Mercury is one of dawning love, proleptic of the receipt of Cupid’s arrow which appears to be aimed particularly at her; which emotion is being recognised, with an expression at once sympathetic, quizzical and apprehensive, by the sister immediately to her left.

The recent discovery of a disguised message (in the floral pattern on the gown of Flora to which Chloris is drawing Zephyr’s attention, see detail below) and related evidence, indicates that the subject matter of La Primavera is set in the context of the Pagan Renaissance Revival championed by Marsilio Ficino, Florence’s foremost philosopher. He was the friend, mentor and tutor of the young Medici owner of the painting, in whom he sought to instill the Platonic philosophy he was introducing to Europe at the time. Ficino’s Platonic teaching held that man possessed a spark of divinity, which contrasted with the medieval view of man’s guilt and culpability.

History.

The origin of the painting is somewhat unclear. It may have been created in response to a request in 1477 of Lorenzo de’ Medici,or it may have been commissioned somewhat later by Lorenzo or his cousin Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici.[22][23] One theory suggests Lorenzo commissioned the portrait to celebrate the birth of his nephew Giulio di Giuliano de’ Medici (who would one day become Pope), but changed his mind after the assassination of Giulo’s father, his brother Giuliano, having it instead completed as a wedding gift for Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici, who married in 1482.

is frequently suggested that Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco is the model for Mercury in the portrait, and his bride Semirande represented as Flora (or Venus).It has also been proposed that the model for Venus was Simonetta Vespucci, wife of Marco Vespucci and perhaps the mistress of Giuliano de’ Medici (who is also sometimes said to have been the model for Mercury).

The painting overall was inspired by a description the Roman poet Ovid wrote of the arrival of Spring (Fasti, Book 5, May 2), though the specifics may have been derived from a poem by Poliziano. As Poliziano’s poem, “Rusticus”, was published in 1483 and the painting is generally held to have been completed around 1482, some scholars have argued that the influence was reversed.

Another inspiration for the painting seems to have been the Lucretius poem “De rerum natura”, which includes the lines, “Spring-time and Venus come, and Venus’ boy, / The winged harbinger, steps on before, / And hard on Zephyr’s foot-prints Mother Flora, / Sprinkling the ways before them, filleth all / With colors and with odors excellent.”

Whatever the truth of its origin and inspiration, the painting was inventoried in the collection of Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici in 1499.Since 1919, it has hung in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. During the Italian campaign of World War Two, the picture was moved to Montegufoni Castle about ten miles south west of Florence to protect it from wartime bombing.

It was returned to the Uffizi Gallery where it remains to the present day.In 1982, the painting was restored. The work has darkened considerably over the course of time.

Duchess d’Orléans, is that the earliest form of the sack-back gown, the robe battante, was invented as

Duchess d’Orléans, is that the earliest form of the sack-back gown, the robe battante, was invented as

seem to have been closely split between two sites. One group, led by

seem to have been closely split between two sites. One group, led by

delicate, Jeanne Hébuterne became a principal subject for Modigliani’s art. In the fall of 1918, the couple moved to the warmer climate of

delicate, Jeanne Hébuterne became a principal subject for Modigliani’s art. In the fall of 1918, the couple moved to the warmer climate of

was the second wife of

was the second wife of  Bella was born in Vitebsk, White Russia, the youngest of eight children of Shmuel Noah and Alta Rosenfeld.

Bella was born in Vitebsk, White Russia, the youngest of eight children of Shmuel Noah and Alta Rosenfeld. Although both were from Vitebsk, their social worlds were far apart and the Rosenfelds were unhappy with the engagement.

Although both were from Vitebsk, their social worlds were far apart and the Rosenfelds were unhappy with the engagement.

nd Egypt, Napoleon took power as First Consul after the coup d’état of 18 Brumaire. In May 1804 he was proclaimed Emperor, and a coronation

nd Egypt, Napoleon took power as First Consul after the coup d’état of 18 Brumaire. In May 1804 he was proclaimed Emperor, and a coronation

and exotic nature. Although symbolism was used in his art forms, it was not at all subtle, and it went far beyond what the imagination during the time frame accepted. Although his work was not widely accepted during his time, some of the pieces that Gustav Klimt did create during his career, are today seen as some of the most important and influential pieces to come out of Austria.

and exotic nature. Although symbolism was used in his art forms, it was not at all subtle, and it went far beyond what the imagination during the time frame accepted. Although his work was not widely accepted during his time, some of the pieces that Gustav Klimt did create during his career, are today seen as some of the most important and influential pieces to come out of Austria. It was most likely Mizzi Zimmermann, model and lover of Gustav Klimt, pregnant at the time, to arouse in him the inspiration for the reason of pregnant women that recurs in his work. During the making of “The Hope” that was again this theme, the son of a year just born from his relationship with Mizzi, Otto, died suddenly.

It was most likely Mizzi Zimmermann, model and lover of Gustav Klimt, pregnant at the time, to arouse in him the inspiration for the reason of pregnant women that recurs in his work. During the making of “The Hope” that was again this theme, the son of a year just born from his relationship with Mizzi, Otto, died suddenly. he spent every summer. Even in 1903 undertook a journey, this time in Italy. Klimt, who in a message of greeting to Emilie Flöge once already had left to go to the exclamation “To hell with words!”, Again was stingy with descriptions of his travel impressions. The phrase “… in Ravenna so much misery – mosaics of unprecedented splendor …” it is to be considered then one of the comments most enthusiastic about art that we know was pronounced by Klimt.

he spent every summer. Even in 1903 undertook a journey, this time in Italy. Klimt, who in a message of greeting to Emilie Flöge once already had left to go to the exclamation “To hell with words!”, Again was stingy with descriptions of his travel impressions. The phrase “… in Ravenna so much misery – mosaics of unprecedented splendor …” it is to be considered then one of the comments most enthusiastic about art that we know was pronounced by Klimt.

Throughout his life, the Dutch painter was able to sell a single painting. His life was marked by poverty and madness, and some remember him as “crazy” but Vincent van Gogh is one of the most celebrated artists in the world.I gathered in this article some curiosity or anecdotes concerning Vincent Van Gogh.

Throughout his life, the Dutch painter was able to sell a single painting. His life was marked by poverty and madness, and some remember him as “crazy” but Vincent van Gogh is one of the most celebrated artists in the world.I gathered in this article some curiosity or anecdotes concerning Vincent Van Gogh. ces tell of seeing him work in some coffee with the strange garment in the head, and the candles stuck in tight or fixed with some bobby pins.

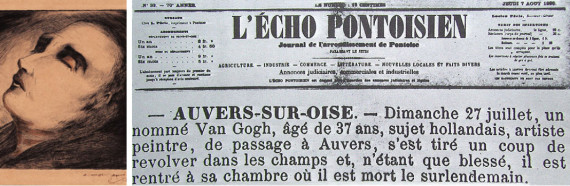

ces tell of seeing him work in some coffee with the strange garment in the head, and the candles stuck in tight or fixed with some bobby pins. In 2011 has released a book titled “Van Gogh: The Life“, written by Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith, biographers and winning a Pulitzer Prize. In this work, the two scholars support the hypothesis that Van Gogh did not commit suicide but was killed by a local boy. Many art historians have never accepted this hypothesis (the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, for example, says that his death was due to suicide). An article, published in November 2014 in Vanity Fair, has rekindled the question: according to the forensic scientist interviewed by the magazine, Van Gogh could not shoot himself because of his hands were never found signs or burns. Biographers Naifeh and Smith insist on one point: the gun was never found. The hypothesis that may have gotten the death is weak also because the artist would have said on several occasions to be against suicide.

In 2011 has released a book titled “Van Gogh: The Life“, written by Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith, biographers and winning a Pulitzer Prize. In this work, the two scholars support the hypothesis that Van Gogh did not commit suicide but was killed by a local boy. Many art historians have never accepted this hypothesis (the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, for example, says that his death was due to suicide). An article, published in November 2014 in Vanity Fair, has rekindled the question: according to the forensic scientist interviewed by the magazine, Van Gogh could not shoot himself because of his hands were never found signs or burns. Biographers Naifeh and Smith insist on one point: the gun was never found. The hypothesis that may have gotten the death is weak also because the artist would have said on several occasions to be against suicide. ating back to just three days after the incident, Van Gogh gave actually a part of the lobe to a prostitute.

ating back to just three days after the incident, Van Gogh gave actually a part of the lobe to a prostitute. In January, 1889, Van Gogh was discharged from the hospital in Arles, where he had been hospitalized after the incident ear. But the artist felt he had recovered completely: his mental health was not yet integrated.

In January, 1889, Van Gogh was discharged from the hospital in Arles, where he had been hospitalized after the incident ear. But the artist felt he had recovered completely: his mental health was not yet integrated. ntings by Van Gogh, as various Sunflowers or The Chamber of Arles, had to be much brighter when it was laid out on the canvas. With time, this pigment unstable went fading, and veered towards brown. Bring it back to the original brilliance can not be, experts say. This would damage the paintings irreversibly.

ntings by Van Gogh, as various Sunflowers or The Chamber of Arles, had to be much brighter when it was laid out on the canvas. With time, this pigment unstable went fading, and veered towards brown. Bring it back to the original brilliance can not be, experts say. This would damage the paintings irreversibly. Before you start painting, Van Gogh was trying to become a teacher or a lawyer. However he pointed to another profession. In a letter of December 1881 he wrote to his brother: “Theo, I am very happy when I paint and I can say that after all he had done last year. My real career in painting is starting now. Do not you think I should follow this passion?” . Van Gogh created more than 900 paintings and 1100 drawings before his death. He was a prolific artist, despite suffering from a form of epilepsy and hypergraphia, a manic tendency to write and, in his case, to paint.

Before you start painting, Van Gogh was trying to become a teacher or a lawyer. However he pointed to another profession. In a letter of December 1881 he wrote to his brother: “Theo, I am very happy when I paint and I can say that after all he had done last year. My real career in painting is starting now. Do not you think I should follow this passion?” . Van Gogh created more than 900 paintings and 1100 drawings before his death. He was a prolific artist, despite suffering from a form of epilepsy and hypergraphia, a manic tendency to write and, in his case, to paint.