In 1917, the House of Romanov had been ruling Russia continuously for more than 300 years when the family was overthrown by the Bolsheviks and Vladimir Lenin. On this date (or possibly yesterday—there’s a debate about exactly when it happened) in 1918, Tsar Nicholas II, along with his wife Alexandra and their five children, met a brutal end: they were shot and stabbed in the basement of the house where they were being held by the Bolsheviks, and the Romanovs’ extended family were either killed or exiled. Nicholas and his family were the last to hold the throne, and their deaths signified a permanent end to the royal family.

Over the years, a number of people have come forward pretending to be exiled members of the Romanov family. Some merely wanted to be famous, while others were convinced that they truly had royal blood coursing through their veins. Today, all members of the immediate family have been identified through DNA evidence as having been killed.

1. Marga Boodts // Claimed to be Olga

After Marga Boodts married a German officer in 1926, she shared a shocking secret: That she was actually Grand Duchess Olga of the Romanovs. Olga was the first daughter of Nicholas and Alexandra, and her hand in marriage was considered very valuable.

Boodts claimed she’d kept the secret because she wasn’t allowed to tell anyone. She said that she was being supported by her uncle, Kaiser Wilhelm II, until his death, and she promised him she wouldn’t tell anyone for “the protection of [her] own life.”

She went public with her claims when Anna Anderson (see below) decided to come out with her own claims of Romanov ancestry. Boodts wanted to destroy Anderson’s credibility while supporting her own. She even wrote aBOOK about everything she had supposedly gone through as a run-away Romanov, but it was never published.

about everything she had supposedly gone through as a run-away Romanov, but it was never published.

Boodts died in 1976 and was buried under the name “Olga Nikolaevna”; the grave was supposedly ruined in 1995.

2. Larissa Tudor // Rumored to be Tatiana

Larissa Tudor married Owen Frederick Morton Tudor in 1923 and lived a very uneventful life with her husband until she died three years later, when she was just 28. Larissa never claimed to be Tatiana, the second daughter in the Romanov family, but rumors arose after her death.

When Larissa died, she left Owen with a large inheritance; its origins were unknown. More than 60 years later, author Michael Occleshaw discovered some inconsistencies in Larissa’s story. He found that she was buried under the name “Larissa Feodorovna,” even though her marriage certificate said “Haouk.” She looked similar to Tatiana and some neighbors, when seeing portraits of Tatiana, said the woman was Larissa.

Occleshaw wrote a book detailing the events and how Tatiana would have escaped and how she could have come to be known as Larissa, although his theory was later disproven.

3 and 4. “Granny” Alina and Ceclava Czapska // Said to be Maria by their grandsons

Alexis Brimeyer also claimed that his grandmother was Maria, but his claims were taken significantly less seriously because he had a history of faking noble titles. He started with “His Serene Highness Prince Khevenhüller-Abensberg,” which he quickly gave up after he was sued by the actual Princess Khevenhüller.

After the legal dust settled, he took on several other names before claiming that his grandmother was actually Maria and that made him a Romanov as well. Brimeyer died in 1995, but not before he also laid claim to the Serbian throne. Until 2007, these conspiracies didn’t seem especially farfetched, because there were a son and daughter missing from the skeletons discovered. But that year, the missing Romanovs were discovered, proving both Brimeyer’s and Alina’s claims false.

5. Anna Anderson, a.k.a. Franziska Shanzkowska // Claimed to be Anastasia

Since 1918, dozens of women have claimed to be Anastasia, the fourth and youngest daughter in the Romanov family, but Anderson is by far the most famous imposter. Her story begins when she tried to commit suicide in Berlin in 1920 and refused to tell anyone her name. Two years later, she began telling people that she was the Grand Duchess.

Some people who knew the Grand Duchess backed up her claims, including family friends and Russian officials. But when relatives of the tsar investigated Anderson’s claims, they discovered that she was actually Franziska Shanzkowska, a woman who had suffered a series of tragic events and had not been heard from since around the time Anderson was found in the canal. Her family later denied her when Nazis threatened to throw her in jail if she was found to be Shanzkowska.

In 1928, she came to live in the United States at the expense of Xenia Leeds, a Russian princess who was distantly related to the Romanovs and living with her American husband. After a failed attempt to claim the Romanov estate, she moved from place to place before ending up in Germany. Once there, she again tried to get ahold of the estate and failed. She returned to the United States in 1968, where she married a wealthy man, and spent her final years in an institutional care facility.

Anderson claimed she was Anastasia until her death in 1984, but DNA evidence proved otherwise in the ’90s.

6. Michael Goleniewski // Claimed to be Alexei

Alexei was the youngest child and only son of Nicholas II, and a real problem for the communist regime in Russia. Like Anastasia, Alexei had quite a few claims to his name.

Michael Goleniewski lived a much less exciting life than Anderson, likely because so few believed his claims. He was born in Poland, and worked as a spy for the Soviet Union while employed for the Polish Secret Service, but he ended up working for the CIA and MI5.

Goleniewski defected to America in 1961 and was made a citizen by a private billpassed by both houses of Congress. Once in the States, he began to claim that he was Tsarevich Alexei and that the rest of the family was alive and in hiding somewhere in Europe. In 1963, Goleniewski had a reunion with another “Anastasia,” a Rhode Island imposter named Eugenia Smith.

Unfortunately for Goleniewski, documents proved he was born and raised in Poland and 18 years younger than Alexei. The tsarevich also had hemophilia, a blood disorder that makes clotting difficult, which was never confirmed in Goleniewski.

The CIA was not happy with Goleniewski for faking something so huge and ended his employment. Still, the wannabe Romanov claimed to know about the tsar’s money and even managed to spark an investigation. Like Anderson, he claimed to be Alexei until his death.

Princess Charlotte Augusta of Wales was the only daughter of

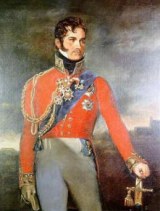

Princess Charlotte Augusta of Wales was the only daughter of  Not surprisingly Charlotte grew up to be a stormy and rebellious teenager. After a failed attempt to force his daughter into a marriage with the Prince of Orange, whom she loathed, the Regent married his daughter and the heiress to the throne to Leopold George Christian Frederick of Saxe-Coburg- Saalfield, (pictured right) her own choice as a husband. Leopold was the youngest child of Francis, Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld and Augusta of Reuss-Ebersdorf. The couple were married on 2 May, 1816, at Carlton House. After spending their honeymoon at Oatlands in Surrey, the country seat of the Duke of York, the couple set up home at Claremont. The cool and collected Leopold was to prove a calming influence on his tempestuous and headstrong wife.

Not surprisingly Charlotte grew up to be a stormy and rebellious teenager. After a failed attempt to force his daughter into a marriage with the Prince of Orange, whom she loathed, the Regent married his daughter and the heiress to the throne to Leopold George Christian Frederick of Saxe-Coburg- Saalfield, (pictured right) her own choice as a husband. Leopold was the youngest child of Francis, Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld and Augusta of Reuss-Ebersdorf. The couple were married on 2 May, 1816, at Carlton House. After spending their honeymoon at Oatlands in Surrey, the country seat of the Duke of York, the couple set up home at Claremont. The cool and collected Leopold was to prove a calming influence on his tempestuous and headstrong wife. After two miscarriages, Charlotte became pregnant with what was hoped would be a grandson and the heir in the next generation to the British throne. She went into labour on 3rd November, 1817. The Prince Regent was summoned and hurried to be present when the labour proved to be difficult and protracted, Caroline’s ordeal lasted for for fifty hours. Finally the child was born at nine o’clock on 6th November, a boy, born dead. The sad news was related to George on his reaching Carlton House, being told that his daughter herself was doing well, he retired exhausted to bed.

After two miscarriages, Charlotte became pregnant with what was hoped would be a grandson and the heir in the next generation to the British throne. She went into labour on 3rd November, 1817. The Prince Regent was summoned and hurried to be present when the labour proved to be difficult and protracted, Caroline’s ordeal lasted for for fifty hours. Finally the child was born at nine o’clock on 6th November, a boy, born dead. The sad news was related to George on his reaching Carlton House, being told that his daughter herself was doing well, he retired exhausted to bed.

When Marie Antoinette died under the heavy blow of the guillotine on Oct. 16, 1793, it was a decidedly unglamorous affair. That’s not to say it wasn’t a celebration: Many French revolutionaries were ecstatic to bid the extravagant queen adieu forever. After the blade came down, the executioner brandished Marie Antoinette’s head in a triumphant wave so that the entire crowd could see it.

When Marie Antoinette died under the heavy blow of the guillotine on Oct. 16, 1793, it was a decidedly unglamorous affair. That’s not to say it wasn’t a celebration: Many French revolutionaries were ecstatic to bid the extravagant queen adieu forever. After the blade came down, the executioner brandished Marie Antoinette’s head in a triumphant wave so that the entire crowd could see it.

Queen Victoria to King Leopold, following Louise’s death. Although Queen Victoria – the doyenne of mourners! – tends to be very over-emotional in all her letters to bereaved people, this letter shows her genuine affection, love and respect for the Queen and for King Leopold and his family:

Queen Victoria to King Leopold, following Louise’s death. Although Queen Victoria – the doyenne of mourners! – tends to be very over-emotional in all her letters to bereaved people, this letter shows her genuine affection, love and respect for the Queen and for King Leopold and his family:

When a gentleman was certain his feelings were reciprocated, he would ask permission of the lady’s parents to pay his addresses. A suitably private setting for the proposal could then be arranged. Most often he would be answered positively since it was very bad form for a lady to encourage an attachment she could not return. Occasionally an unwelcome proposal might be made despite her lack of encouragement, and then the lady would have to turn her suitor down but always with sensitivity to the man’s feelings.

When a gentleman was certain his feelings were reciprocated, he would ask permission of the lady’s parents to pay his addresses. A suitably private setting for the proposal could then be arranged. Most often he would be answered positively since it was very bad form for a lady to encourage an attachment she could not return. Occasionally an unwelcome proposal might be made despite her lack of encouragement, and then the lady would have to turn her suitor down but always with sensitivity to the man’s feelings.